POSTCARDS FROM MARK TWAIN

IT CAN BE no exaggeration to say that my collection of postcards, luggage labels, matches, menus, brochures, ashtrays, keyrings, soaps, shower caps and other memorabilia of Bristol hotels was the largest in the world. But it was the postcards that I liked best. Dating from the 1880s to the present day, they included views of interiors long since refurbished, views that have been lost to new buildings and traffic, and many fine buildings no longer standing. It was a wonderful visual story of a small but not insignificant aspect of the hospitality industry.

For several years I spent my spare time rummaging through boxes on market stalls, visiting bric-à-brac and antiquarian bookshops, trawling the internet and making regularly visits to eBay, developing a network of worldwide suppliers. At first, whenever I stayed in a Bristol, I would send a postcard of the hotel to Sophie, but when I realised that she was throwing them away, I addressed them to myself at the London office.

Sophie never understood the excitement of collecting nor did she appreciate the increasing value of these acquisitions. I promised her that I would get rid of them as soon as I could find a suitable archive or depository, but the real reason I procrastinated is that I had other plans for the Tom Cotton Collection. Once I could be sure that I had a postcard of every Hotel Bristol that ever existed, I intended to locate them all on a map of the world and have them mounted for a travelling exhibition that could go on display in the foyers of every hotel called Bristol around the world.

Of course I don’t know what happened to the postcards in the end, and probably never will find out, but nothing would make me happier than one day walking into a Hotel Bristol and seeing my idea brought to fruition.

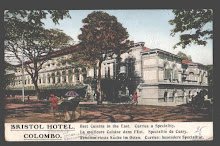

Among my collection were several old postcards of the Hotel Bristol in Colombo, Sri Lanka, or what was then Ceylon, and the frequency with which these turned up is not surprising because A.W.A. Plâté, the man who took the pictures, had his photographic studio in the hotel. A handsome colonial building in the Raffles mould, the Bristol Hotel on the postcard was in a dusty looking street with no traffic except for an unoccupied rickshaw that stood in the shade of a jacaranda. Nothing much was going on. It appeared to be a very restful spot and I am sure that it would have been a pleasure to sip a pink gin beneath its pavement awning, or settle down to a curry from the “Best cuisine in the East – Curries a Speciality”. This boast, in English, French and German, is on a hand-coloured card in my possession, which adds the further claim that room rates were “moderate”. Even from this distance I can hear the gentle cajoling of a white-jacketed waiter touting for custom, and I am beguiled by his sales pitch.

The Hotel Bristol no longer exists, but the name of the man who took the pictures is immortalised in millions of postcards of the hotel, the island and other parts of Asia. A.W.A. Plâté was an apothecary before he was a photographer. He and his wife Clara set up a studio in the hotel in 1890 and the pictures and postcards they produced for guests and tourists over the following two years as they travelled around Southeast Asia were so successful that the couple moved to a building in Colpetty, which they named the Bristol Studio. This became the finest photographic establishment in the East, and it was soon producing half a million postcards a year. Plâté & Co was in business at the same address until 1974.

THERE IS something evocative about black-and-white photography. It is a mature medium that conveys both innocence and honesty, showing not just another time but a place and people without time. Images are completely trapped in the frame with no wish or way to escape. How many hotels and travellers’ haunts were photographed like this, in crisp monochrome, their streets ignorant of traffic jams, the unhurried people made for the early cameras’ long exposures? In even the smallest villages around the world today bars and cafés like to put up enlarged prints of postcards showing how their communities looked, how their people dressed, before they were discoloured by industry, wars, tourism and homogenous clothing. Though Hungary’s was the first postal system to accept the idea of postcards, it was the picture of Gustav Eiffel’s astonishing Tower in the Paris Exhibition of 1889, celebrating the centenary of the French Revolution, that began seriously to fill mail bags, inscribed with spidery writing so familiar to relatives and so hard for us to decipher today. I have been here, and seen this. This is my hotel.

This is not to say that colour photography is not wonderful. But by the time it appeared the world was becoming a different place. The contrast between the two provided an dividing line, throwing the monochrome world into the past and giving it a patina of romance. Perhaps we like to think of the past without colour, just as we like our Greek and Roman temples unpainted, not gaudy as they really were. Black-and-white studio portraits are the images we have of our great grandparents, and it is often the way we picture famous people, too, even colourful artists like Monet and Matisse.

I imagine Mark Twain in black-and-white. His grizzled thick grey hair and walrus whiskers were made for monochrome. The creator of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn stayed at the Hotel Bristol in Colombo at the same time that A.W.A. Plâté started taking photographs. He was on a world lecture tour of the British Empire, as a lack of linguistic skills prevented him from entertaining non-English speaking audiences. He needed the money because he had just lost $100,000 investing in a worthless venture concerning a typesetting machine. It is not difficult to imagine him in a white linen suit, dusting off his hat and settling down at the bar with a bourbon, his unruly hair tickled by the cooling draughts of the ceiling fan. All in monochrome.

He wrote down his experience of the journey in Follow the Equator, published in 1896, and it is clear that he saw the Bristol Hotel, the town, its people and the whole island of Serendipity not as a monotonous postcard, but in a blindingly colourful light:

January 13. Unspeakably hot. The equator is arriving again. We are within eight degrees of it. Ceylon present. Dear me, it is beautiful! And most sumptuously tropical, as to character of foliage and opulence of it. “What though the spicy breezes blow soft o’er Ceylon’s isle” – an eloquent line, an incomparable line; it says little, but conveys whole libraries of sentiment, and Oriental charm and mystery, and tropic deliciousness – a line that quivers and tingles with a thousand unexpressed and inexpressible things, things that haunt one and find no articulate voice… Colombo, the capital. An Oriental town, most manifestly; and fascinating.

January 14. Hotel Bristol. Servant Brompy. Alert, gentle, smiling, winning young brown creature as ever was. Beautiful shining black hair combed back like a woman’s, and knotted at the back of his head – tortoise-shell comb in it, sign that he is a Singhalese; slender, shapely form; jacket; under it is a beltless and flowing white cotton gown – from neck straight to heel; he and his outfit quite unmasculine. It was an embarrassment to undress before him.

We drove to the market, using the Japanese jinriksha – our first acquaintanceship with it. It is a light cart, with a native to draw it. He makes good speed for half-an-hour, but it is hard work for him; he is too slight for it. After the half-hour there is no more pleasure for you; your attention is all on the man, just as it would be on a tired horse, and necessarily your sympathy is there too. There’s a plenty of these ’rickshas, and the tariff is incredibly cheap…

The drive through the town and out to the Galle Face by the seashore, what a dream it was of tropical splendors of bloom and blossom, and Oriental conflagrations of costume! The walking groups of men, women, boys, girls, babies – each individual was a flame, each group a house afire for color. And such stunning colors, such intensely vivid colors, such rich and exquisite minglings and fusings of rainbows and lightnings! And all harmonious, all in perfect taste; never a discordant note; never a color on any person swearing at another color on him or failing to harmonize faultlessly with the colors of any group the wearer might join. The stuffs were silk-thin, soft, delicate, clinging; and, as a rule, each piece a solid color: a splendid green, a splendid blue, a splendid yellow, a splendid purple, a splendid ruby, deep, and rich with smouldering fires they swept continuously by in crowds and legions and multitudes, glowing, flashing, burning, radiant; and every five seconds came a burst of blinding red that made a body catch his breath, and filled his heart with joy. And then, the unimaginable grace of those costumes! Sometimes a woman’s whole dress was but a scarf wound about her person and her head, sometimes a man’s was but a turban and a careless rag or two - in both cases generous areas of polished dark skin showing – but always the arrangement compelled the homage of the eye and made the heart sing for gladness.

I can see it to this day, that radiant panorama, that wilderness of rich color, that incomparable dissolving-view of harmonious tints, and lithe half-covered forms, and beautiful brown faces, and gracious and graceful gestures and attitudes and movements, free, unstudied, barren of stiffness and restraint, and – Just then, into this dream of fairyland and paradise a grating dissonance was injected.

Out of a missionary school came marching, two and two, sixteen prim and pious little Christian black girls, Europeanly clothed – dressed, to the last detail, as they would have been dressed on a summer Sunday in an English or American village. Those clothes – oh, they were unspeakably ugly! Ugly, barbarous, destitute of taste, destitute of grace, repulsive as a shroud. I looked at my womenfolk’s clothes – just full-grown duplicates of the outrages disguising those poor little abused creatures – and was ashamed to be seen in the street with them. Then I looked at my own clothes, and was ashamed to be seen in the street with myself.

However, we must put up with our clothes as they are – they have their reason for existing. They are on us to expose us – to advertise what we wear them to conceal. They are a sign; a sign of insincerity; a sign of suppressed vanity; a pretense that we despise gorgeous colors and the graces of harmony and form; and we put them on to propagate that lie and back it up. But we do not deceive our neighbor; and when we step into Ceylon we realize that we have not even deceived ourselves. We do love brilliant colors and graceful costumes; and at home we will turn out in a storm to see them when the procession goes by – and envy the wearers. We go to the theater to look at them and grieve that we can’t be clothed like that. We go to the King’s ball, when we get a chance, and are glad of a sight of the splendid uniforms and the glittering orders. When we are granted permission to attend an imperial drawing-room we shut ourselves up in private and parade around in the theatrical court-dress by the hour, and admire ourselves in the glass, and are utterly happy; and every member of every governor’s staff in democratic America does the same with his grand new uniform – and if he is not watched he will get himself photographed in it, too. When I see the Lord Mayor’s footman I am dissatisfied with my lot. Yes, our clothes are a lie, and have been nothing short of that these hundred years. They are insincere, they are the ugly and appropriate outward exposure of an inward sham and a moral decay.

The last little brown boy I chanced to notice in the crowds and swarms of Colombo had nothing on but a twine string around his waist, but in my memory the frank honesty of his costume still stands out in pleasant contrast with the odious flummery in which the little Sunday-school dowdies were masquerading.

OF COURSE you couldn’t write all that on the back of a postcard. You would have to send an email. But electronic mail doesn’t give you the full picture, and nobody is interested in collecting it.